Why Would Anyone Pay? and other FAQs

(...in progress)

Why would anyone pay if they do not have to?

How

can FairPay boost sales volume, revenue and profit?

But why would anyone pay more than just enough?

What

other factors might push buyers to pay especially well?

Is this a guessing game, or would there be

suggested prices to guide buyers and increase seller control?

Won't buyers just psych out the system and drive a race to the bottom?

Won't cutting off those who pay too little anger many customers?

Does FairPay work across vendors, and does it apply to one-time sales?

Would FairPay be used as a special offer or go on indefinitely?

Will FairPay

coexist with conventional pricing?

Can't buyers game the FairPay reputation system by buying under different

false IDs?

Is this too much

to expect buyers to understand?

Isn't having to think about setting prices going to be burdensome?

What kinds of

businesses would this work for, in what forms?

Can you be more specific about how FairPay might work in a specific

context?

How hard is

it to implement a FairPay pricing system? How do I start?

What is the

status of FairPay as a business offering?

Have there been field trials or behavioral economics studies to support this

idea?

Why would anyone pay if they do not have to?

The answer is simple: Buyers who do not pay

will not get further offers.

This is the first question many people ask on

hearing of FairPay -- given its core of Pay What You Want (PWYW) pricing.

It is an important question, and a central feature of FairPay is the

FairPay reputation feedback process that addresses that. With FairPay, there are consequences for not

paying -- much as there are for getting a poor credit rating. (But it

should be understood that even with

simple PWYW,

few buyers pay zero, and many pay a reasonable price, even without the

feedback controls of FairPay.)

FairPay will generally be

most useful in cases where there is an ongoing

relationship between the buyer and one or more sellers. This might be for

ongoing purchases of multiple items or services, or for ongoing subscription

access, taking the form of

a series of limited FairPay offers from the seller in response to a series of FairPay pricing

actions by the buyer.

Sellers can be expected to limit the initial FairPay offers

that they extend to new customers who lack established FairPay reputations.

They might offer only items and quantities that might typically be free

(much as with freemium pricing), so

that their risk is small. Only after the buyer establishes a history of

paying fairly will the seller continue to make FairPay offers for larger

quantities or premium items. The benefits to the buyer of not paying will be

limited and short-lived. The benefits of paying will continue and

grow.

Sellers can be expected to make these

consequences clear when they first extend an offer to sell on a FairPay

basis. This framing of the offer may be one of the most important

opportunities to set the stage for good behavior. The product/service is not offered as "free," nor as simple PWYW, but

as Fair PWYW, or perhaps better put as Pay What You Think Fair

-- essentially on trial, on approval, and on evaluation.

Perhaps the theme might be that buyers

should "pay nicely" -- and sellers will play nicely in return.

Sellers would

make it clear that zero is "acceptable" -- with regard to reputation and

future consequences -- only when that is arguably fair. Such cases of

reasonable fairness in setting a zero price might include cases in which the

buyer gives a reason why there is little or no realized value to the buyer

(much as is often required for returns), or where only very low quantities

are sampled (which might be conventionally understood as a buyer-directed

form of free sampling).

Of course a poor reputation need not be

irredeemable. Just as recency factors into credit ratings, FairPay

reputations would likely consider recency, as well. Even someone who

behaved badly some time ago might be given another chance some time later.

Care can be taken to assure buyers that they will not be "blackballed"

unfairly, without an opportunity to explain or show good faith.

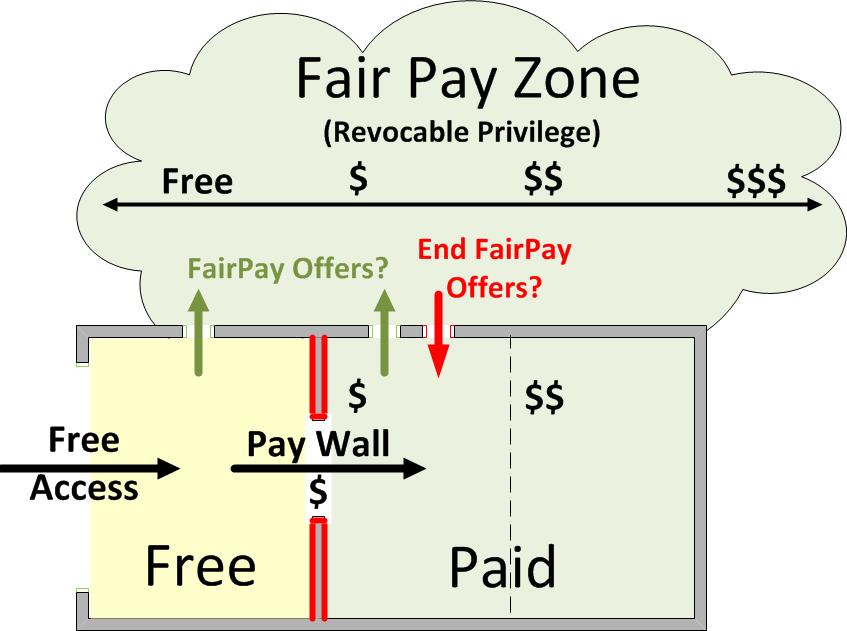

This process may be clearest and work best for

early uses of FairPay that are complementary to "freemium" offerings

-- which

combine limited access to free products/services with a "pay wall" that

requires set price payments for more usage and/or premium items. As an

alternative to the pay wall and its set prices, buyers may be invited to

enter a "FairPay Zone" and permitted to stay there as long as they pay

fairly, as depicted in this

diagram

(click for more commentary):

How

can FairPay boost sales volume and revenue and profit?

One of the important benefits of FairPay is that

it can potentially lead to dramatic increases in sales volume, and can

increase both revenue and profit significantly. As shown is

studies of PWYW pricing, such buyer-set pricing can result in lower average prices, but

in many cases it can increase sales so much that revenue and profit increase

dramatically. One recent study showed a variant of PWYW that

increased sales by nearly a factor of ten, and increased profit by a factor

of three. Of course FairPay should do even better than PWYW, by

adding incentives to pay fairly.

(See Isaac, Gneezy references)

Buyers typically have widely different

perceptions of value and willingness to pay. Set prices deter many

potential buyers who question that the product/service is worth that price to

them. FairPay largely removes that barrier (letting them try the

product and set the price to a level they are willing to pay), and thus enables sales to many added buyers who

might find the product valuable, and who might decide to pay enough to be

profitable, even if not the full standard price. This greater self-selection effect has been

referred to in economic studies of PWYW as "endogenous price

discrimination" (See Isaac

reference)

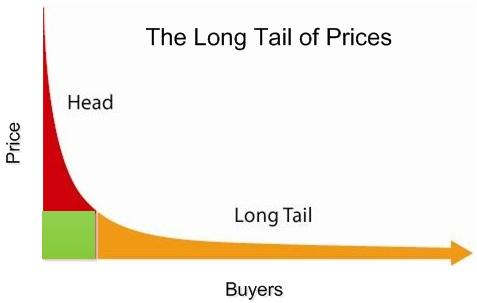

A graphic view of how this self-selecting price

discrimination feature of FairPay might dramatically expand revenue capture

is given in The FairPay Zone blog post "The

Long Tail of Prices -- Uncoil it with FairPay" The green area

shows the revenue under standard pricing. The red and amber areas show

potential revenue that is lost under standard pricing, but can be realized

with FairPay.

But why would anyone pay more than just enough?

The details of how to get good pricing levels will vary

for any given seller and product, but in

general, buyer behavior can be pushed to increasingly desirable levels by sellers that manage

their customer relationship well. Some of this is basic mechanics, and

some gets to broader issues.

One basic factor is that much pricing of digital

content is done on a flat-rate, "all-you-can-eat" basis because consumers

seem to prefer that to a ticking usage meter, even if that is economically

inefficient on both sides. FairPay allows buyers to not feel enslaved

by usage meters, but to view usage reports as guidance in

setting their prices. Thus buyers who are heavy users, and/or who use

lots of premium items or services, will recognize that they should pay at

relatively high rates -- possibly more than they would under conventional

flat-rate pricing.

More generally, being eligible for future FairPay offers

can be positioned as not a simple yes or no decision, but one with many

levels. Buyers might be told that those who pay better than average

will get enhanced offers, those who pay below average will get bare-bones

FairPay offers. This might relate to larger amounts of

product being made available before a price must be set, access to more premium item types, or other perks.

In this respect, FairPay can behave much like freemium.

This might be similar to the perks in frequent

flyer programs that provide upgrades, visible recognition and status, and

other special privileges. Such methods might even include making some

aspects of good payment behavior visible as a status symbol (possibly only

for those buyers who seek that kind of "conspicuous FairPayment").

Such perks might be pre-designated, but some hints of surprise bonuses.

Such expectations of surprise effects might entice buyers and make it less

desirable to try to "psych out" the process to minimize payments.

Also, a good FairPay reputation might depend not

only on how well you pay, but on how well you explain why you pay especially

well or poorly in specific cases. This would give the seller valuable feedback

not just on pricing, but on the merits of their product. Buyers might be

given visible recognition for such thoughtful feedback (such as badges)

naming them as elite partners, a form of status reward (like top ranked

reviewers on Amazon) that consumers might seek to earn and display (with

little fear of being seen as crass).

Such methods might be useful not only to move

average payers to pay more, but to convert bargain-hunters to be less

fixated on price and more on relationship and value.

What

other factors might push buyers to pay especially well?

FairPay also gets to fundamental questions of how

businesses relate to their customers, and whether they can change the

"conversation" from a zero-sum game of which party can get the most from the

other and give the least, to a win-win game, where both parties seek a

mutually beneficial value exchange. Society seems to be broadly seeking a

more win-win kind of market, and that is just what FairPay is all about.

Recent behavioral economics findings and

experiments with PWYW pricing have added weight to these ideas.

As noted for the previous question, sellers might find various ways to

directly incentivize good payments with perks and better deals, but there

are many other factors that can add to this as well.

Related to the ideas in The Cluetrain Manifesto

of markets as "conversations," Dan Pink's book "Drive" summarizes how current trends are pushing toward

more win-win behaviors, building on three motivations: autonomy, mastery,

and purpose. FairPay helps

change marketplace dialog to exploit exactly those motivations, by giving

buyers much more autonomy, opportunities to develop mastery, and ability to

reflect their purpose into their pricing decisions. Sellers who position

themselves as partners in value exchange, frame their FairPay offers

thoughtfully, and work with their customers as partners seeking mutual

benefit, will succeed in getting them to pay fairly. Those who do not may

find it difficult.

A related aspect of this is how well the seller can

position the price paid as being a well-deserved compensation for value

creation, and necessary to ensure a continuing supply of value. This

obviously factors into the modest success of musicians and game developers

with conventional PWYW sales (as for the Radiohead album sale -- why did so many pay more than one cent,

and some more than the usual standard price?).

Such

positioning is relatively easy for sellers who can claim that most of the

price goes to compensation to artists, journalists, or other human

contributors. It is also likely to benefit companies that, like Apple, are

perceived as being focused on consumer value, or who are recognized for

superior service, or for other kinds of social

benefit, such as green/sustainable, charitable, etc. Favorable positioning may be more of a challenge

for companies that are perceived negatively, or simply as commodity

suppliers, especially if not compensated by superior service or other

positives.

The addition of charitable

elements has been shown is some recent research on PWYW to very effective in

discouraging free-riding. Charity tie-ins might be very effective with FairPay as well.

(See Gneezy reference)

Is this a guessing game, or would there be suggested prices to guide buyers

and increase seller control?

There are a wide variety of pricing cues that

can be provided, and this is an area in which experimentation and ingenuity

may be useful to find the best ways to set mutual expectations.

Obviously complex behavioral issues are involved here. But in general,

FairPay is a dialog that will probably work best with a high degree of

openness about decisions and expectations.

Suggested prices may be very desirable, and

conventional set prices may also be a good reference point. Depending

on context, suggested prices might be lower than set prices but in some

situations they might be higher. For example a newspaper might have

unlimited subscriptions for $5/month on a conventional basis, and might

suggest that light users pay somewhat less than that and the heavy users pay

somewhat more, and that those that value their unique journalism add a

premium contribution. Similarly those that use only basic features

might be suggested to pay less, those that use many premium features to pay

more.

Of course there could also be minimum prices as

well, in a more limited form of FairPay. While this might be desirable

in some contexts (such as where marginal costs are high or free-riding is a

big concern), doing that would reduce the appeal of FairPay as a way to give

buyers a feeling of freedom and partnership, and confidence that they will

not suffer buyer's remorse.

Sellers might also provide reference data on how

other buyers have set their prices. These might be averages, or richer

views of the distribution of payments (such as 25, 50, and 75 percentiles).

Any of these kinds of reference prices might be

set to correspond to the usage and market segments that the buyer belongs

to, such as reflecting levels of light or heavy usage, basic or

advanced/premium services, and demographic/psychographic segments, including

affluence or student/professional status, etc. By framing offers and

guiding pricing decisions appropriately, sellers might gain the effect of

segmentations that are far more flexible and adaptive than conventional

set-price segmentation schemes.

This concept of framing is the same as that of

using "choice architectures" to "nudge" decisions while maintaining freedom

to choose (as explored in the book Nudge, by Thaler and Sunstein)

A particularly attractive method is described in

a

blog post on how suggested prices might be combined with pricing set

in terms of a differential above or below the suggested price to seek

relatively high control and predictability over buyer-set prices.

Such methods facilitate framing dialog on pricing fairness in terms

consistent with the seller's perspective.

Won't buyers just psych out the system and drive a race to the bottom?

Won't the pricing cutoff criteria get out on the

Internet?

Won't those who find out others paid less be unhappy?

The flexibility and nuance of how FairPay is

applied on an individual, dynamic basis can minimize such concerns.

There may well be a segment of bargain hunters

who will work hard to find the lowest prices a seller will tolerate.

But, depending on the market, that segment might be only 10-50% of the total

market. With FairPay, a seller can serve the highly price-conscious

market, and generate some profit from them, and, at the same time,

incentivize those who are more value-conscious to share a larger portion of

their economic "surplus."

FairPay is not as easy to psych out as it may

seem, because the lower bound is not uniform, but varies based on the

customer usage context -- it probably does not work well to disclose a

specific lower bound -- what I suggest is to give guidelines on what the

lower bound is a function of, with a fuzzy range of suggested/reference

prices under some relevant conditions of usage and satisfaction, but leave

it open-ended. (And of course in an online world, detailed usage and

context data is readily applied as a basis for pricing dialog.)

Furthermore, those who pay well are less likely

to feel suckered, because the offer management and price request process

will frame the pricing decision in terms of the particular aspects of their

usage, and of the level of premium services or perks they receive.

Unlike conventional dynamic prices (like airlines) that are unilaterally set

by the seller, the FairPay price is set by the buyer, so it inherently

cannot not be deemed unfair by the buyer -- the argument for price

differentiation becomes a shared/negotiated argument.

The heart of achieving this is to tailor the

offer, and to communicate its framing, such that the user understands the

factors affecting a fair dynamic/individualized price (for both buyer and

seller), and can make judgments in that context (understanding that other

buyers may deserve different prices given different circumstances). The

seller's rules can evolve over time and learning, and the seller can tailor

the offer to the buyer. (The rules can be further nuanced, such as with the

fuzzy logic, neural nets, etc. as used in credit management and fraud

alerting).

-

One example is for newspaper

subscriptions or e-books. Here usage becomes one key dynamic factor --

if I never finish a book, I might reasonably pay little. If I refer to

it regularly I should pay more. If I read 200 news articles/month I

should be willing to pay more than one who reads 40. Again, more for

business/finance, less for general interest. More for affluent, etc.

-

A more advanced example

might apply to considerations such as in airline pricing. I might be OK

with paying more for last minute seats held for a premium price for last

minute travel, but less for excess seats that would go empty. I might

pay more if business, less if retired/student. More for no-bump, less

for bump at will. Price discrimination is not objectionable if the buyer

gets to agree to the rationale for it (with a conventional set-price

option as fallback if the two sides diverge).

Thus, FairPay can be tuned and framed to work for all

segments, using a well-designed and customized "choice architecture." FairPay should be especially attractive to

price-conscious buyers who are reluctant to pay the set price, and to

relatively generous and fairness-conscious buyers who might pay more than

the set price (if warranted). Recent research on PWYW pricing supports

the idea that such effects can be significant and can lead to significantly

higher revenue and profit. (See Isaac, Gneezy, Chen

references.)

Won't cutting off those who pay too little anger many customers?

Rarely, if managed with care. There can be

warnings, probations (with continuation of only more limited value offers),

etc., to nudge those honestly seeking to play nicely, before sending them

back to the set-price fallback. By framing FairPay as a privilege,

possibly as a membership program or club, the contingency and

responsibilities of the privilege can be made as clear as the benefits.

Does FairPay work across vendors, and does it apply to one-time sales?

Another factor that can strengthen the

effectiveness of FairPay, as it develops, would be the emergence of shared FairPay infrastructures among multiple vendors

to enable cross-vendor

collection and sharing of reputation data. This

infrastructure might behave much like cross-vendor credit reporting and

rating services. Just as with credit reports, consumers will be more

inclined to behave well to avoid harming a FairPay pricing reputation that

many vendors will rely on.

Such cross-vendor uses of FairPay would also

extend its applicability, in that vendors might make offers in situations

likely to be one-time sales, and still get significant benefits from FairPay.

By using shared reputations derived from previous transactions with other

sellers, vendors can decide whether to extend the offer to a customer who is

new to them. At the same

time, knowing that reports of their pricing experience would go to other

vendors would provide strong incentive for the buyer to pay fairly, even

with no expectation of further purchases from that one vendor.

In a single-vendor context, FairPay can be

expected to be most effective where there is an ongoing relationship, such

as for repeat purchases, or subscriptions. Sellers will presumably want to

apply Fairpay primarily in contexts where such an ongoing relationship is

likely (either with them, or through a multi-vendor FairPay network).

Would FairPay be used as a special offer or go on indefinitely?

In general, ongoing use would seem desirable.

As long as buyers pay fairly, both parties should be happy. The buyer

maintains maximum freedom and flexibility, and the seller has a happy

customer who pays fairly -- and many more who do the same -- thus hopefully

maximizing revenue and profit. Of course the

process can end, whether across the board, or for individual buyers.

-

Overall, a seller may

decide that, in his market, this method is just not the best -- and might

switch to a more conventional process, or might limit its use in various

ways.

-

With respect to specific

buyers, either side might decide they prefer conventional pricing as

producing better deals -- or as good enough and simpler.

-

Sellers may find it

desirable to use FairPay only for introductory and light use, or for

sampling, and they might require that regular,

heavy users pay conventionally.

Finding out how FairPay works

relative to conventional alternatives in specific businesses, for specific customer

segments, will be a learning process. Sometimes FairPay will not turn

out to be best, and sometimes buyers and/or sellers will have difficulty

getting it right. Complex behavioral issues are involved, and will

vary in different contexts.

Results will also vary depending

on how well offers are framed and how well relationships are managed.

Sellers who do not manage that part well may find conventional pricing

simpler and more

suited to their business.

Will FairPay

coexist with conventional pricing?

FairPay may often coexist

with conventional pricing options, as an optional variation (or as a fallback).

-

Some buyers may just prefer

the simplicity of a set price.

-

Many sellers will find it

best to have set-priced options as an alternative (and/or a penalty) for

those who do not play nicely under FairPay, or who are reluctant to try

it.

-

By positioning FairPay as

a more flexible, buyer-controlled alternative to conventional pricing,

sellers can entice buyers to put in the modest effort needed to consider

this new idea.

Combined use may be

especially valuable as a way for the seller to benefit from price-conscious

buyers who are reluctant to pay the set price, and from relatively generous

and fairness-conscious buyers who might pay more than the set price (if

warranted). Recent research on PWYW pricing supports the idea that

such effects can be significant and can lead to significantly higher revenue

and profit. (See Chen reference.)

Can't buyers game the FairPay reputation system by buying under different

false IDs?

To a degree, but this can be limited to tolerable levels by

-

using various

ID mechanisms, and by

-

limiting the value-at-risk

outstanding at a given time for any buyer who lacks a

well-established positive reputation.

As with all

reputation systems, new participants are most safely

treated as having low reputation until they demonstrate

otherwise (and once established over time, good reputations are

not lightly sacrificed). The ID problem is much

the same as for conventional pricing systems that allow

some free usage (such as a small number of newspaper

articles), then charge for more. Expanding on some

of these points:

-

A

user's Internet device IP

address can be a moderately good identifier, and

can be determined with no burden to the buyer.

(Services can be used to inexpensively detect and

reject anonymous addresses obtained through

proxies.)

-

Credit cards are widely used to verify identity

(including name and address), without making any

charge, and this adds only a modest hurdle to

buyers.

-

To

manage identity risk, a seller might typically limit

users who have yet to establish good FairPay

reputations to low value offers. These might

be for small numbers of items, and only for low

value item types, and then, as good experience is

gained, gradually extended to offer more FairPay

"credit" covering larger quantities and more premium

item types, as noted just above.

-

Other

fraud protection methods used in e-commerce can also

be applied.

Is this too much

to expect buyers to understand?

That is a concern, but one that we suggest can

be managed, and once past an initial learning curve, buyers will find it to

be liberating and natural.

Of course it will be important to educate buyers

and sellers in how FairPay transactions can work and why they are

desirable. FairPay turns many traditional ideas about pricing upside down,

and shifts considerable responsibility to the buyer. Sellers will need to

provide buyers with clear explanation of the basic process, and how and why

their pricing should be fair. A

Sample FairPay Offer is provided (for the example of a newspaper

subscription) to suggest how this might be done.

Sellers will need to carefully frame their

specific FairPay offers to set expectations on value and responsibilities,

to define relevant usage metrics, and to facilitate buyer pricing

decisions. It will be important to do this well, and to keep early

implementations as simple as possible -- but there is no reason why it can't

be made reasonably simple, in many useful contexts.

Also, it seems likely that most uses of FairPay

will be as complements to conventional pricing options. So to the extent

there is a learning barrier for FairPay, in such cases it will simply push

customers to the conventional set-price option, rather than turn them away.

By positioning FairPay as a more flexible alternative to the standard price

offer, many buyers may be motivated to take the trouble to understand how to

exploit that more attractive option.

Once buyers and sellers experience the

flexibility and nuance that can be realized with FairPay dialog processes,

they will come to see how it can actually be more intuitive and sensible

than conventional methods. FairPay can liberate both buyers and

sellers from the rigidity of conventional pricing, and enable a new level of

fluency in pricing.

Isn't having to think about setting prices going to be burdensome?

That is a critical design issue for sellers --

to be successful, a FairPay system must

be designed to be very painless for buyers to use.

What this means is that payment decisions for

very small

purchases need to be aggregated. FairPay will generally not work well if

buyers must think about pricing a single Web page or song or video clip. But it

can work well for a subscription or other bulk purchase (such as a bundle of

songs or videos or e-books or apps). This is how

most people pay now for mobile phones and cable TV – not per item, but per

month, for some large basket of items. FairPay

subscriptions might be paid monthly, and once consumers have established

good FairPay reputations, price setting might be done only annually.

Similarly, buyers could be offered bundles of items, with further bundles to

be made available after the prices are set and judged acceptable for the

previous bundle.

The better and more

well-established your FairPay

reputation, the more freedom you will have to buy a large number of items on

“approval”, and then review a usage “statement” and settle up infrequently,

with relatively low burden (much like having a high credit limit and

extended payment terms on a credit card)

What kinds of

businesses would this work for, in what forms?

How far through our economy this method can go

and exactly what forms it will take

remains to be seen.

-

A sweet spot for initial use, and the area of most urgent need,

is clearly in digital products and services. Particularly good candidates for

FairPay may include:

-

services that are

currently free, but where the seller feels urgent

need to begin charging (such as newspapers and many

video services), or

-

services that are so

pressured for revenue that conventional PWYW is a

serious consideration, in spite of its high risks (such as for music and video games), or

-

services that now charge

a high rate, and seek to broaden their market with a

more limited FairPay option for low-end market

segments.

-

FairPay it is also applicable to physical products and services,

as well, especially for those with low marginal cost (such as CDs/DVDs), or with low cost tie-ins

(such as product service and support, and other product related services). PWYW

has been found (references) to be effective for some kinds

physical products (especially as a way to attract

new customers), so FairPay should perform even

better.

A working paper on

FairPay Application/Market Segments summarizes how various specific

business segments might apply FairPay processes.

As is apparent, there are complex behavioral

issues, learning curves on the part of both sellers and buyers, and an

infinite variety of buyer/seller/product/service contexts that will affect

the pricing process. We can expect that FairPay will start with

relatively simple processes in a few business segments, and that it will

spread and gain in sophistication as experience is gained,

FairPay pricing processes can be applied by

individual providers of products/services, or more broadly as cross-vendor

networks of FairPay sellers that pool FairPay reputation data much as credit

reporting is done across vendors. FairPay infrastructures can be

developed by individual seller businesses, or by platform providers to such

businesses.

Can you be more specific about how FairPay might work in a specific

context?

Sure. Please see the working paper on

FairPay Application/Market Segments

(mentioned for the previous question) for links to blog posts that explore

specific business use cases, and check the

FairPay Zone Blog for recent additions. Some brief examples are

also given in

the introductory article on

FairPay.

How hard is

it to implement a FairPay pricing system? How do I start?

Depending on the business context and the level

of sophistication desired, implementation effort can range from very simple

to reasonably complex. In many contexts, useful FairPay implementations

can be done by an individual seller company without great effort.

As a very beneficial partial step toward

FairPay, one option is to introduce FairPay in just a survey mode,

in which transactions are done conventionally but buyers can indicate if

they feel they should pay more or less, and give their reasons. Such a

survey mode can generate valuable data on customers, and begin a mode of

dialog that can set the stage for full use of FairPay. This lets a

seller get his toes wet by starting a structured dialog with buyers about

what they want and how they value it, without need to integrate with live

pricing systems or put any revenue at risk.

Cross-vendor FairPay platform services can

build the infrastructure for managing offers, tracking pricing actions,

and maintaining reputation databases, and make that available to even

low-end sellers to exploit with simple Web services. Such cross-vendor

services can also pool FairPay reputation data, so that even small sellers

might have access to high value reputation data on large numbers of buyers,

even for one-time sales.

If you are interested in starting to use

FairPay pricing processes, please

contact us.

What is the

status of FairPay as a business offering?

Current information is now in the

Overview.

Have there been field trials or behavioral economics studies to support this

idea?

Current information is now in the

Overview.

Behavioral economic research

on PWYW and related pricing issues, and studies and reports on field trials

of PWYW in various forms are very supportive of the value of FairPay as

described here. There have been numerous studies of PWYW in both

real-world and theoretic contexts, and their findings indicate that such

methods can be far more effective than many people might expect.

Selected references are discussed in the

Resource Guide to Pricing.

(Working Draft revised 8/15/10, 10/5/10, 6/27/11,

7/18/11, 10/17/11, 12/14/15) |